For centuries, the pyramids of the Maya world have loomed over the jungles of Guatemala — silent, overgrown, their secrets swallowed by vines and time. These monuments were not just tombs or temples, but stages for power, ritual, and myth. And in 2013, inside one of these pyramids at Holmul in the Petén region, archaeologists uncovered something astonishing: a monumental stucco frieze, brilliantly preserved, that told of alliances, betrayals, and a clash between ancient superpowers.

The discovery would reshape how historians viewed the 6th-century Maya world. What appeared at first to be exquisite art turned out to be something far more: political propaganda carved into stone, a statement of loyalty in a struggle between two kingdoms — Tikal and the Snake Lords of Kaanul.

A Hidden Masterpiece Beneath the Stones

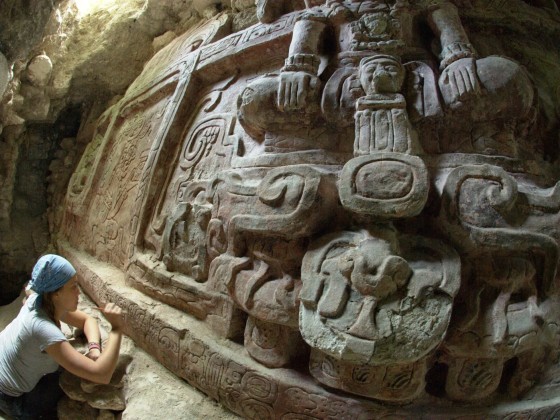

The frieze emerged by accident. Archaeologist Francisco Estrada-Belli and his team were excavating a 65-foot pyramid, hoping to find Preclassic remains dating back to 250 BCE. Instead, beneath later construction, they uncovered the upper walls of a Classic-period structure — decorated with stucco figures eight meters long and two meters high.

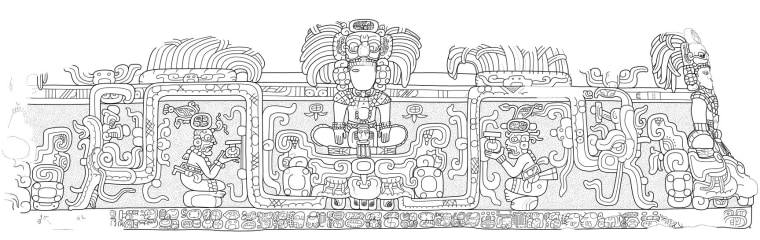

Three lords sit cross-legged, draped in jade and crowned with bird headdresses, poised above the head of a mountain spirit. From that spirit’s mouth, two feathered serpents coil upward, embracing a pair of deities holding signs that proclaim “First Tamale.” Below runs a band of glyphs — nearly thirty in total — identifying the building’s commissioner: Ajwosaj Chan K’inich of Naranjo, a vassal of the Snake King of Kaanul.

For Estrada-Belli, the meaning was immediate. “This wasn’t local squabbling,” he explained. “This was empire building. The frieze ties Holmul not to itself, but to a superpower beyond its walls.”

The Rivalry of Giants: Tikal vs. Kaanul

To understand the carving, one must step into the turbulent politics of the 6th century. Tikal, the great city of the central lowlands, had long dominated the region. But in 562 CE, Tikal suffered a crushing defeat — a turning point historians call the “hiatus,” when its influence waned. Rising in its shadow were the Snake Lords of Kaanul, based in Calakmul.

The Holmul frieze, dated around 590 CE, sits squarely in this moment. It portrays Ajwosaj Chan K’inich not as an independent ruler but as the loyal servant of the Snake King. His commission of the building was less a personal act of devotion than a declaration: Holmul, once tied to Tikal, now bent to Kaanul authority.

This was propaganda on a monumental scale — stone, stucco, and paint transformed into a political billboard proclaiming allegiance in the superpower struggle of the Classic Maya.

Decoding the Glyphs

Harvard epigrapher Alex Tokovinine, who helped decipher the inscription, emphasized its clarity. “It names Ajwosaj as a vassal of the Snake King,” he noted. “It situates Holmul in a web of alliances designed to contain and challenge Tikal.”

The reference to “First Tamale” — a ritual food tied to creation myths — suggests not only politics but also religion. By evoking sacred imagery, the frieze sanctified Ajwosaj’s rule and legitimized Kaanul dominance. It was not enough to conquer; one had to rewrite cosmic order in stone.

A Wider Theater of War and Influence

The Holmul find aligns with discoveries elsewhere. At El Perú-Waka, west of Tikal, other inscriptions describe Snake Lord expansion, revealing a coordinated campaign on multiple fronts. The Holmul frieze represents the eastern flank of this empire building.

David Freidel of Washington University, a leading figure in the El Perú-Waka project, observed: “What Estrada-Belli discovered shows how the conquest of Tikal was celebrated far from its heartland. These weren’t isolated cities; they were chess pieces in a regional game of power.”

Art, Power, and Propaganda

The artistry of the frieze cannot be separated from its politics. Stucco carvings of such scale were expensive, requiring skilled artisans and enormous labor. To commission such work was to signal wealth, legitimacy, and divine favor.

Every headdress, every serpent, every glyph reinforced hierarchy. The mountain spirit suggested dominion over the natural world, the serpents evoked Kaanul’s dynastic emblem, and the deified figures tied present rulers to mythic ancestors. To stand before the frieze in the 6th century was to be enveloped by a story that left no room for doubt: Holmul belonged to the Snake Lords.

Mysteries Beneath the Pyramid

Yet for all its revelations, the frieze raises new questions. Nearby, archaeologists uncovered the undisturbed tomb of a high-status man, his teeth inlaid with jade beads, his mask carved of wood. Was he Ajwosaj himself, entombed within the propaganda he commissioned? Or was he another lord, aligned with the shifting tides of power?

The pyramid that sheltered the frieze was itself later buried beneath another structure in the 8th century. Why? Was the propaganda erased by shifting alliances, or preserved as a foundation for new rulers? The answers remain hidden, awaiting future excavations.

Echoes of the Snake

The symbolism of snakes in Maya culture carries layers of meaning. They were creatures of the underworld, mediators between realms, emblems of power and transformation. For the Kaanul dynasty to brand itself as the Snake Kingdom was to claim cosmic authority.

To carve serpents rising from a mountain spirit was not only to assert military control but also to root that control in divine order. The frieze declared: Kaanul does not merely rule Holmul — it rules by the mandate of the cosmos.

Lessons from Holmul

The Holmul frieze reminds us that history is not only recorded in chronicles but also etched in stone. It shows the sophistication of Classic Maya politics — not a chaotic swirl of warlords, but organized states with long-term strategies. It demonstrates the use of art as a weapon, as effective as any spear or shield.

And it underscores the fragility of power. Just as Tikal fell and Kaanul rose, so too did Kaanul eventually fall, its monuments left to the jungle, its propaganda eroded into mystery.

Conclusion: A Silent Witness in the Jungle

Today, the Holmul frieze sits buried again, preserved against looters and rain. Its figures — lords in bird headdresses, serpents coiled in stucco — still whisper of a time when two great powers struggled for dominance, and even small cities like Holmul were drawn into the orbit of empire.

For archaeologists, it is both a treasure and a challenge, a reminder that every pyramid may hold another chapter of history waiting to be uncovered. For the rest of us, it is a window into the resilience of human ambition, the universality of power struggles, and the enduring truth that art is never only art — it is memory, message, and monument.

Sources

-

NBC News – “Inside a Maya pyramid, mysterious carvings hint at superpower struggle”

-

National Geographic – Maya frieze found in Guatemala

-

Harvard University, Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions Project

-

Smithsonian Magazine – Classic Maya Politics and Power